It was a bid to become unrecognizable. She had first determined she was a man, then she had determined she was a woman. As a man she had been serious, lonesome, studious, and dedicated to her academic work. As a woman she was capricious, gregarious, and a careful listener. She wandered a lot, but not in meadows or forests, rather between men’s homes in two major boroughs of the biggest city in America, New York.

The Commissioner, as she called herself, would come home sometimes, nevertheless, to her own room. It was situated at the Midwood-Flatbush border of Brooklyn, where the rent was relatively inexpensive. Her apartment was flanked by a wealthy Orthodox Jewish neighborhood to the South, and a Caribbean neighborhood to the North and East. On the West side was a Bengali and Pakistani neighborhood, and a bit to the North was a white suburb filled with small Victorian mansions. Sometimes she fancied herself the Commissioner of any of New York City’s major departments—the Commissioner of the Department of Buildings, or the Commissioner of the Department of Parks, or the Commissioner of the Department of Sanitation. She liked the idea of being a “public servant,” though she was an unemployed academic.

Her project, in moving to the city, and away from small-town university life, was to have sex with as many men as possible, and in tandem with this act, to write about it, and to support herself by becoming a kind of mercenary employee, someone hired for small but important jobs, someone whose general aptitude for research would make her seem amenable to a range of work. She had considered becoming a sex worker, but realized that being a sex worker would take something fundamental out of her conquests, which was the sense, for the victim, that he himself was engaged in a conquest of his own. So she trudged on, often unemployed, living off savings she had made as an undergraduate office worker, and as a graduate student with a stipend.

Back in her room, after about 24 hours spent with her latest lover, No. 20, she thought about all that had happened since she had become the Commissioner, since she had become a public-servant-in-training to New York City. The most recent event, it seemed, was that someone she had slept with once and went to bed with several times, but ultimately rejected, No. 17, had just invited her to his housewarming party, and she felt, as she read the invitation, next to her newest lover, that the fall-out of that relationship had created a sense of strain or alienation around the whole endeavor of promiscuity. No. 17 hadn’t been compatible with her on so many fronts, though they had one strong thing in common: the ability to converse endlessly about people, and about what they desired. He, on account of his dissatisfaction with her “seductive behavior,” combined with his ability to convey his dissatisfaction in absolute terms, had convinced her to see her reality in serious detail.

Presently, she slept in four different beds. She had that of No. 20, in Sunset Park. No. 20 had very little in common when it came to discursive, academic frameworks, but they did have one shared practice: they’d create make-believe roles in the context of sex. They were always coming up with new names and titles for one another—Ms. Park, the Commissioner, the Chief, the Chief’s daughter, the Commissioner’s Son, the Chief of Staff of the DSNY, the Daughter of the DSNY. He was, moreover, “adorable,” and he liked to read and write.

After No. 20, there was No. 18, and No. 7. No. 7 was her ex, her “gramps,” her “babby”—a play on “daddy”—and he lived in a central Lower Manhattan one-bedroom apartment. She’d roll her bike into the lobby on some days, after analysis, recognized by all the doormen, and take the elevator up to the fifth floor, where No. 7—a small, intense, thin, angular man with blue eyes and blond hair—would greet her with a tight hug and affectionate words from their jointly formed dialect. Then she’d do some work on her laptop in the living room, hooked up to an external monitor she owned and had brought there when she had lived with him, and cook or shower. Sometimes she’d stay the night, sleeping on the living room floor, on a sheepskin. They rarely, if ever, had sex anymore, and he was her main confidant, the person with whom she’d discuss most of her going-ons with other people. One of those objects of gossip was No. 18, a man she had been dating for about two months, who bore a few superficial similarities with No. 7. Both were half-Jewish, had divorced parents, and worked in finance. Other than that, they were almost the opposite, temperamentally and physically. No. 18 was tall, lean and athletic, dark-haired, and easy-going to the point of a frictionless neutrality. He had large blue eyes that made him seem innocent and adorable, like the pokémon Azumarill. The Commissioner had started to lose interest in No. 18 after about two months of seeing him, but she still sought him out at his Wall Street apartment once a week, as if primarily to debrief about her going-ons with No. 20, and to hear about his going-ons with his other women. So in this way, the Commissioner spent her nights in four different beds, retiring to her own place just three nights a week, for she’d often see No. 20 twice. Her week went something like this: Sunday at No. 18’s, Monday alone, Tuesday with No. 7, Wednesday alone, Thursday alone, Friday with No. 20, Saturday with No. 20. Each of these four different beds corresponded to different sceneries and processes for leaving the house the next morning: walking up Wall, Pine, Broadway, Cedar, and Church to 3 World Trade Center with No. 18, walking to the Union Square Whole Foods for groceries while staying with No. 7, or biking to the ferry from Sunset Park to get to analysis in FiDi after a night with No. 20.

The Commissioner’s active lifestyle left her wanting to go to sleep on her downtime. It was tough to keep her eyes open when she was alone, which didn’t, in theory, bother her. But she felt she wasn’t able to do her job. What was her job? To observe, and to make something of these observations. To have proof that she was having effects on others' lives. Felicitous effects, meaningful effects. Otherwise, to “commission” things that had yet to exist. It felt like making something out of nothing, it was a Herculean task, to do one’s job while not knowing what one’s job responsibilities were. Being an unemployed academic was wearing on her.

When she arrived back in her apartment, she’d find her room in disarray: garments strewn across the bed, old tea leaves in the kyūsu, numerous coffee- or tea-stained cups to rinse out, tepid water with a bit of dust or oil on the surface, a plate with an apple core or crumbs left on it set on the floor near the door. She did wash her cups and plates and cook for herself in due course, but it was hard to begin these processes sometimes, even hours after having returned. It was always messy because leaving her house involved not only deciding what clothes to wear, but packing extra items, like a change of underwear or toiletries or a laptop, and then carrying the bike and a loaded pannier down the stairs, careful not to scratch the walls. The ride from Brooklyn to Manhattan took between 40 and 50 minutes, depending on where she was headed. On rarer occassions, she’d bike for 30 minutes through Borough Park to get to Sunset Park, but often, she’d go there from Manhattan.

One week, in apparent revolt, she didn’t see No. 18. She only saw No. 20 for one continuous span of 24 hours, not two continuous spans of 24 hours, or one continuous span of 48. She spent one long night at No. 7’s place. She hadn’t slept in his living room for a while. It was clear to her that she wanted to return to her past, to her life with No. 7, and for the first time, she could see the beauty in doing so. She had lived with him, for a year, and experienced both immense comfort and immense boredom. Now, in her exhaustion, and in her desire to make herself useful, employed, she wished for comfort, and couldn’t imagine being bored. But now she was the Commissioner. With No. 7, she hadn’t been the Commissioner—she had been Chomie, or Gomo, or Bibi. A little girl, his daughter, his “sugar babby.” She knew she couldn’t go back to being with him, at least not yet, for if she did, she’d leave again, to fly off to some other man, with whom she could experience more outward struggles, more of the vicissitudes of life. Still, she pined after the year she had spent with him, and felt so acutely her identification with his location, between 8th and 9th street, and University Place and Broadway.

But she went home. And then, she went to No. 20. And then, she went back home, where she sat to write. It was twenty-something hours after her last encounter with No. 20, as the Commissioner sat at her desk, in a powerful silence, reading and writing for her diaristic website. She checked her calendar. It had been the ninth encounter with No. 20, or Cherry, as she had begun to call him, that Saturday, leading into Sunday.

Cherry’s last name was Muzsik, which meant man, or peasant, in Hungarian. He was from Throggs Neck, a more white and middle-class suburb of the Bronx, a little peninsula which connected to Queens over a bridge. He had been a line cook for a while before finishing a degree in physics. He had attended something like four different CUNY colleges throughout his twenties, and become a software engineer for Dow Jones in his early 30s. Now he was 34. He knew that his ancestors had been in the Bronx for many generations, that he was mostly of English heritage. There were some German names in his family tree, none of them Jewish.

The first night she slept with Cherry, she dreamt of a sheaf of papers, the manuscript of a novel. She had been reading it, and at some point paused, noticing that the page numbers were out of order. But she hadn’t detected any discontinuity in the story, so she wondered if it was right to rearrange the papers. Maybe the story would make sense anyway, with the order rearranged. But then she’d lose the version she had read.

When she brought the dream in to her analysis, she began with the obvious claim that the dream seemed to reveal how important the enumeration of her lovers was to her. It was essential that No. 18 preceded No. 20. That seventeen lovers had come before No. 18, and that there was one lover between No. 18 and No. 20.

Her analyst then asked a funny question. “Who’s your favorite lover?”

“Cherry,” she said, almost immediately. “Cherry, though I’ve only met him twice.”

The Commissioner broke into a smile, and continued.

It was strange, too, because she knew she preferred Jewish men.

She had explained earlier that she had once dated a real, Christian man, who claimed he wasn’t observant, but used to write articles for a Christian magazine. On the surface, they seemed like they might fit together: he was a therapist in psychoanalytic training, he liked movies she liked, he had a degree in literature, he also liked Peter Handke. This man, No. 15, also had a website, where he wrote diaristic entries about being abroad, and about his attempts to be with various women. She liked his earnestness, plainspoken ways, but also sensed a kind of arrogance in him. Something about the way he spoke about his long walks, about his alone time. This man, quite rigid and serious, had ultimately provoked her to break up with him by demonstrating concern, only five dates in, that she was continuing to see No. 7.

This Christian man, No. 15, was in turn an echo of No. 17, who evinced a similarly serious desire to be with someone he deemed his match, his equal, in a monogamous fashion, No. 17 desired a “partner.”

This was the core of the colonial mindset, the missionary mindset, she said.

“And what do you see in Jewish men?”

“I guess there’s A’s idea of irony, of an ironic religiosity. That you just do things, you just observe traditions, even if you don’t fundamentally believe that they’ll take you anywhere. They won’t lead to anything ‘higher,’ but you still find it important to do these things, knowing nevertheless that they won’t ‘uplift’ you.”

“I guess I’ll have to think about it more, though. I suppose I believe that this mindset would lead more naturally to the development of a critical, inquisitive mind, capable of noticing or constructing a multiplicity of meanings in some scene of experience. No final judgment. No necessary or sufficient unity.”

“But obviously there’s more than one way of being a Christian man.”

“Obviously?”

Cherry, as it turned out, also had a practice of writing on a personal website, which he had designed from scratch. It took the Commissioner several dates to discover this—three, to be precise—and by the fourth date, she came to him with a new sense of trust. She liked what she had found. It wasn’t so much the objective, eternal material of the text that she liked, but the energy, the speed, the clarity of gesture evinced by the collection of diary entries and transcriptions of ostensibly real conversations he had recorded.

Easily, though, Cherry had fallen into a certain stereotype that had been imprinted in the Commissioner’s psyche. First, there had been No. 2. No. 2 and the Commissioner met in high school, and began to correspond over email and letter in college, when she was in the thick of her studious, isolated manhood. In addition to writing emails and letters, he had maintained a personal website, and later created several more, each tailored to more specific series of short fiction. Tthe correspondence quickly stirred romantic feeling in them both.

But he was a high, serious, monastic sort of man, blond and severe, so dedicated to work, it seemed, or to some kind of hallowed solitude, or to some nostalgia for a version of the Commissioner that no longer existed. He rejected further intimacy when she desired it most. Was it because she was male? On account of the suffering which gripped her in No. 2’s wake, she sought out psychoanalysis. Psychoanalysis! Within the first six months of the treatment, she came to the decision to stop taking testosterone, and to leave behind her eight or so years as a transgender man. It was if she were returning to the time when she had first met No. 2, still a girl of uncertain identity. As a newly minted, twenty-four year old woman, however, she realized she was attractive enought to meet and sleep with many strangers, and she thus began to leave the centrality of No. 2 behind.

During this time, she began to call herself Judith. She wrote about her novel experiences in rigorous detail on her website. She felt that her writing about these encounters with strangers from dating apps derived from, and often consummated, a passion for knowledge, recognizable from her graduate studies, but of a different tenor.

She felt dedicated, in a way that had never stuck before. And she knew she had a relationship with a reader. Judith knew that No. 2, her website’s primary reader, had begun to feel badly about her choice to exclude him as a participant in her tales. Often, she felt like a cruel mistress, writing purely in order to cuckold him, purely in order to cut off his metaphyiscal head. But her cruel joys were tempered by the fact, which she was well aware of, that she had given him a position of great privilege by making him the central reader.

She slowly moved on from the vengeful tenor of her writing. As the frisson of cruelty and revenge wore off, Judith became much more circumspect about her diaristic notebook, and less interested in writing down the details of each encounter with a new man. Though she enjoyed the business of getting to know each new man, she lamented the fact that she was failing to write about sex, sex itself, in a way that would interest her.

Cherry was stimulating, inspiring her to write again, and maybe differently, about sex.

He had come up with the title, “Commissioner.” He had seen it on a building code sign in a café, and she noted in him hence a particular genius for spontaneous creation. “Cherry.” It rhymed with his given name, and perfectly evoked his deliciousness, his adorable physical form, the muscular roundness of his buttocks, strong from playing soccer. Calling him “Cherry” made the Commissioner feel like a “predatory older woman.”

She encouraged him to have multiple girlfriends, and to write about his encounters on his website, which he did, once, successfully. Having passed the little test, he was eligible to read her website. And now that he had, it was her responsibility to come up with a new piece of writing, one which would impress him, or more precisely, impress upon him a better sense of who she was. She was the Commissioner. She was Judith. She was someone who had no identity outside of abstraction, outside of her desire and often successful attempts to abstract herself out of an appearance or situation. She was also someone with a concrete, stable desire to kill the beloved, to behead and castrate him, but only if she adored him enough to want to take care of his cadaver. She told Cherry this on the first date, when they were lolling in bed at her apartment. She had also told No. 18., who she had really wanted to maim. On the first date, she left him with a hickey on his neck.

Most of all, she loved the feeling of having fucked. She was easily responsive to him, to his hands and mouth and cock and his insistent movements, and she loved Cherry in association with the strong, gratifying orgasms she’d experience with him, orgasms which she thought of as the experience of getting flattened out, of being a polygon of some kind, like a pentagon or septagon or nonagon or hendecagon. “Once flattened, your edges explode, you fill space, you’re undefined space, that’s what an orgasm is,” she sadi to him the third time they met. From then on she began to think of him more acutely as her “favorite lover.” Cherry might’ve sensed it, and asked her to come over on a weeknight to write and study, so she came, bearing with her two Hanukkah doughnuts, sufganiyot, from her favorite Union Square bakery. The fourth time was even better, so five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten, eleven more times, they came together in coitus, with her orgasm or his or both at the same time ending their sessions. The Commissioner allowed him to fuck her without a condom. He called her Ms. Park, the Commissioner, and the Commissioner’s daughter. He left copious ejaculate on her body and sometimes dripped semen as he was pulling out, from the semi-orgasms that resulted from trying to hold back. It was hot, but she was worried, and after the seventh encounter she worried some more.

There was nothing hotter, really, than the risk of successful intrusion.

But it worried her, so she began to think about what it would mean to be with No. 20.

She began to The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism.

Max Weber confirmed and clarified some of what she had experienced with her men: No. 15, No. 17, and No. 2. The Protestant ethic involved the desire to respond to a singular calling, and to work towards that single aim, in relation to the notion that one would ultimately appear before the scene of a final and univocal judgment. Protestant hermeneutics arose from loneliness, a righteous loneliness. And with that loneliness, she surmised, the desire to find a single partner who shared in this loneliness. God’s grace is, since His decrees cannot change, as impossible for those to whom He has granted it to lose as it is unattainable for those to whom He has denied it. In its extreme inhumanity this doctrine must above all have had one consequence for the life of a generation which surrendered to its magnificent consistency. That was a feeling of unprecedented inner loneliness of the single individual. (Weber 60).

By what method could she surmise that any of her men truly felt this way? It would be necessary to stipulate that Weber’s argument focused on the extremity of the Calvinist logic, and that No. 15 and No. 2 had more Lutheranism in their blood, that No. 17’s religious background was a mystery to her, and that No. 20 was the closest she might get to a kind of Calvinism, if only because she could see so well his interest in loneliness and work, and in the kind of humbleness that goes along with this—but was this truly a Calvinist ethic?

She started to menstruate, but the relief from the scare only reinforced her sense of an enduring ideological divide. She wrote about her concerns in vague and terrifying language. Then, in clearer terms: I don’t believe in a higher calling, or work for work’s sake. I don’t believe in fitness, in strengthening myself, or in maintaining my goodness. I don’t believe in literature, in creative production. I just want to be able to die in my own fashion.

On the ninth date with Cherry she came to break up with him. As she readied herself, she turned away, and began to cry a little. But she couldn’t continue, not with the crying, and not with the speech. The absence of sadness in the room kept her from understanding the tragic impulses which had brought her to her decision.

He touched her a little, which caused her to break into a smirk and a grin, which she exaggerated by turning her face down until her eyes and nose and mouth were completely foreshortened, flattened into three inches of visible face. It was one of her favorite expressions, the “look of evil,” and he knew it. He pulled her close and she kissed his cheek, and straddled him, and he put his hands up the front of her sweater. She pouted, in an exaggeratedly cute way, that made her eyes and lips and nose look like a collection of droplets. She was still sitting on his lap, and pushing him against the chair he leant on, until he got off and lay on the floor. The two of them were so aroused, and so happy, they pressed their organs together without taking their clothes off.

Soon, they went out and played soccer, and then ate “bullwhip soup” at a Taiwanese restaurant filled with Americana, including license plates from various states. Then they went a Teso Life, where Cherry bought a Korean toothpaste that turned out to be pine-flavored, and more Japanese 002 condoms. She thought they must have looked like a happy couple. She felt happy, and kept on looking at him, her favorite lover.

Cherry would depart he next day for a week-long vacation, and proposed that he give her license to inhabit his apartment in the mean time. He made copies of his keys at the store nearby, the one which sometimes burned their trash—newspapers and magazines—right outside. She jangled her four foreign keys, two of them No. 7’s, two of them No. 20’s, gladly, and the night after he left, she texted him to say she was taking the N train down to Sunset Park. She had noticed that everyone on the train appeared to be either Chinese or Central American. The train was fast, only making a few stops: 14th, Canal, Atlantic Av, 36 St, 59 St, and then 8th Av. Appearing to blend in, she felt uneasy, she felt she was an impostor. For someone with such a strong sense of self based on coins, stickers, and logos, or debased, cut-off sexual organs like the “pusie” or “cunt,” she was quite exaggeratedly perturbed by questions of ethnic origin. The Brooklyn Chinese district was uncannily redolent of her mother’s culture, as it was more Fujianese than Cantonese, and as she learned that day, Fuzhou was right by Taiwan. Many of the rice cakes on the street looked familiar to her, and the bakeries sold sweets that seemed more like what her mother might like to eat than the Cantonese bakeries in Manhattan’s Chinatown. They were a little more Japanese, that was one way of seeing it. The pastries had subtle markers of Japanese influence and there were a few Japanese stores clearly meant to cater to Chinese consumers. She could hear more Mandarin on the streets, and the Fuzhou dialect, or the Hakka dialect, sounded more like the dialect her mother’s mother spoke. The Commissioner knew little about her maternal line and often claimed to be the most American woman in the world, the absolute most American. She was ruthlessly unattached to the continent from which her forefathers had come, she had no identity beyond her manifest activities.

It couldn’t be experienced by her with neutrality; it had the atmosphere of a primal scene; it had too much to do with her, her mother, her denial of an ethnic identity. She hoped that the Chinese women of Sunset Park, the cashiers at the bakeries and grocery stores at which Cherry had been a regular, would see her as a Korean woman. A total foreigner, an intruder. Nevertheless, she uttered a few words in Mandarin, more than she had in a decade, more than she had spoken even in Taiwan. A few days earlier, she had told Cherry about nián gāo (年糕) and asked a street vendor a question in Mandarin, to confirm that the 年糕 she was selling had hóng dòu (紅豆) in it. The woman vendor named her price, and also told her to try something else that was white and globular, probably some sort of fish ball. Gesturing at Cherry, she said something in Mandarin, which led the Commissioner to translate: “She’s saying that you will never have tried this before. But neither have I!”

The night after he left, she arrived at 8th Ave all alone, and went out and bought some celtuce and green onions. She thanked the cashier in Mandarin. She made a soup with pork spare ribs, which she had bought at Hmart in Midtown, assuming correctly that the meat stores would be closed when she got back at 8 PM. She cooked noodles and celtuce with the meat and ate while revising some writing she had been working on, her mind unsentimental and focused. While she cooked, she saw that No. 2 had sent her a story he had written.

She read it with her spare rib soup. She thought of suggesting that he begin it near where it had ended, when the narrator manages to articulate her problem. No. 2 might achieve a certain freedom by beginning from what he called the detente, and seeing what could be written in its aftermath. She wanted him not to end with the knot but to begin with it, to unravel instead of tighten the thing to its close. Many of the jittering words in the exposition seemed too fragile, too transparently brittle; they were thin glossy defenses over a “loamy” soft tissue of emotions beneath, which the Commissioner didn’t see any reason to be embarrassed about.

She was familiar with his struggles through time spent with him and emails received, and felt strongly, on account of her experience of having written to him in a state of distress and utter loneliness, that writing wasn’t going to make things better, that one had better write while in better spirits. She liked reading what he wrote whe she could sense his underlying well-being. This story felt sickly, etiolated, baroquely withering.

But maybe it was his calling, to write stories, however he wanted to, and in the lowest of moods. And this was his style, his chosen style, and she knew she must respect his affliction and the manner of his affliction.

She walked home, across Borough Park, to the Flatbush-Midwood border four miles away. During the long, ninety-minute walk, she tried to overhear conversations. A few men spoke on their phones in Yiddish. A girl speaking to another girl spoke in frustrated, rapid-fire anaphora of not wanting to do three different things. What were these things? Her obligations, to school, to family? The Commissioner admired the speed and force of her statements. She heard an older woman speak in a Brooklyn dialect of English, which sounded so practical, tool-like, like a scissor. She was very happy to be walking among the Jews, as usual, and thought that several of the women she had seen had been very pretty. The men, that day, not so much. She had seen attractive Hasidic men but they never struck her as any more handsome than the other men she had known. Maybe her appreciation of the women felt stronger, however, because she so rarely appreciated women.

She also saw snow, totalled cars, bonsai trees with wires coiled around the branches.

Walking home, she enjoyed feeling a sense of duty to the exegetical mindset, so it was from that sort of mood of devotion that she wrote. It was fun, naughty, to study as if devout and pious but to not belong to a well-defined tradition. One had to figure out not just what one cared for, but how one wanted to go about it.

She thought of the fact that No. 2 had a father of Norwegian descent. She hadn’t asked and hadn’t thought much about his religious inheritance when she was getting to know him, but she thought of it now. The Norwegians were Lutherans, no? His mom, with her Italian surname, might’ve had more of a Catholic lineage, though she had no sense of the mother’s maternal line. Anyway, these weren’t Calvinist sects.

Still, it was impossible not to see the basic, prayer-like gesture in his writing, the idea that the work, or the success of the work, meant that one was destined to be saved and redeemed. The story’s primary voice in fact mentioned something about “projects,” about “hating projects,” which to the Commissioner implied No. 2’s deep enmeshment in projects, in what could be called, in more theological terms, his calling.

And he, she thought, was clearly attracted to others who evinced a relationship with a calling. Stupefying intelligence, it seemed, implied and corresponded to dedication to a craft, and that craft was a calling, an attempt to please God. And was she one of them, one of the Elect? Not necessarily under the severe logical gauntlet of Calvinism, but under a more “traditionalist” Lutheranism, bent less on the accumulation of profit but on a steady dedication to some sort of humble but intricate craft? No, no, no. She refused this.

She reclined in her Oriental way on a sheepskin as she read, imagining herself as a subject for a Nineteenth century French painting of a belle juive. It was a dark, gilded, sensual, voluptuous knowledge that she claimed for herself. It was the knowledge of the cunt, the knowledge of the whore. The first consistent boyfriend she had had after No. 2 was a lackadaisical Jewish man, and he, No. 4, had introduced her to the concept of the shikse. He was, apparently, the first Asian woman he had slept with; before, he had been in Russia, seemingly in pursuit of an adoptive motherland. His mother, from a photo, appeared to her to be uniquely beautiful, and she saw that he resembled her closely. No. 4 did not like his mother, however, because she had been disabled for much of his adolescence and all of his adult life, by Parkinson’s disease, a common affliction among Ashkenazi Jews. “My father’s father also had Parkinson’s,” she told him, and he was surprised, as if only Ashekanzi Jews could have it. He wasn’t sure he could ever be with a Jewish woman, he said that day.

In this she heard a familiar narrative, of repudiating one’s familial origins in favor of something foreign but familiar. From the on they began, really began to have their uneven, casual, but rather close relationship; she felt he was her adoptive mother. No. 4 often left her hanging, ejaculating too soon, and because he was less driven to physical intimacy than she was, he very nearly drove her mad in the end, as her dissatisfaction accumulated and hardened into a final, violent act. She cut, she cut the floor with a knife, and bent the knife until it was permanently bent. This was provoked by one particularly close, but missed orgasm, at the very end of her time in the university town. From then on really understood herself to be Judith, as close as she could legally get to the slaying of Holofernes. She had felt so dulled by his dumb silences, and did not understand why she was so drawn to shadowing his life habits, when she often found them so dissatisfying, but she knew it was for the crushing terror of being left hanging again and again. Long outings looking for birds, long mornings sitting on the porch, where it was often a bit too wet or cold, going to bed early and rising early to look for birds, his tendency to not want to sleep with her either in the morning or at night. The deep and devastating horniness that sustained her simmering ire, which made her tell herself, God hates me, God hates me.

Her wretchedness was soon replaced by a series of keen friendships. She found No. 7, her next Jewish man. A year later, she found No. 18, who was No. 7’s rhyme. Again, he was half-Jewish, with a shikse mother who had converted, divorced parents, and a job in finance. These two men seemed to welcome her into herself, into her fundamental mode or method, into a kind of pious attentiveness to her self as sexual being.

She came to recognize in her regular acts that sex, with its character of effacement and expenditure, sex with the exhaustion and deadening of the man, stood against creation, and thus stood against the way of life that her Mother had inculcated in her. With sex, she stole most of a man’s life force each time.

The Commissioner had become Judith once more. But she was changed; her considerations of the Christians had changed her. She had become like a horse in a D.H. Lawrence novel, with its eyes flashing and its nostrils flaring, or like one of his yellow-eyed women, Ursula from Women in Love. She was reading for a second time Thomas Hardy’s story of Bathsheba Everdene, and thought of Diana, or ἀρτεμής, the “stainless maiden,” “she who shoots arrows.” This she had been, in her imagination, as a child. But now she felt devout, and voluptuous, in the odd secret conviction of being a lost and wandering Jew. She had felt it first while reading Freud, while she came to love the way he tripped and hesitated and posited, as in his elaboration of the drive as a border-concept between the mental and the physical. And she had recognized it again in a commentary on Freud by Harold Bloom: “Jewish dualism is neither the split between body and soul, nor the abyss between subject and object […] rather it is the ceaseless agon within the self not only against all outward injustice but also against what might be called the injustice of outwardness or, more simply, the way things are.”

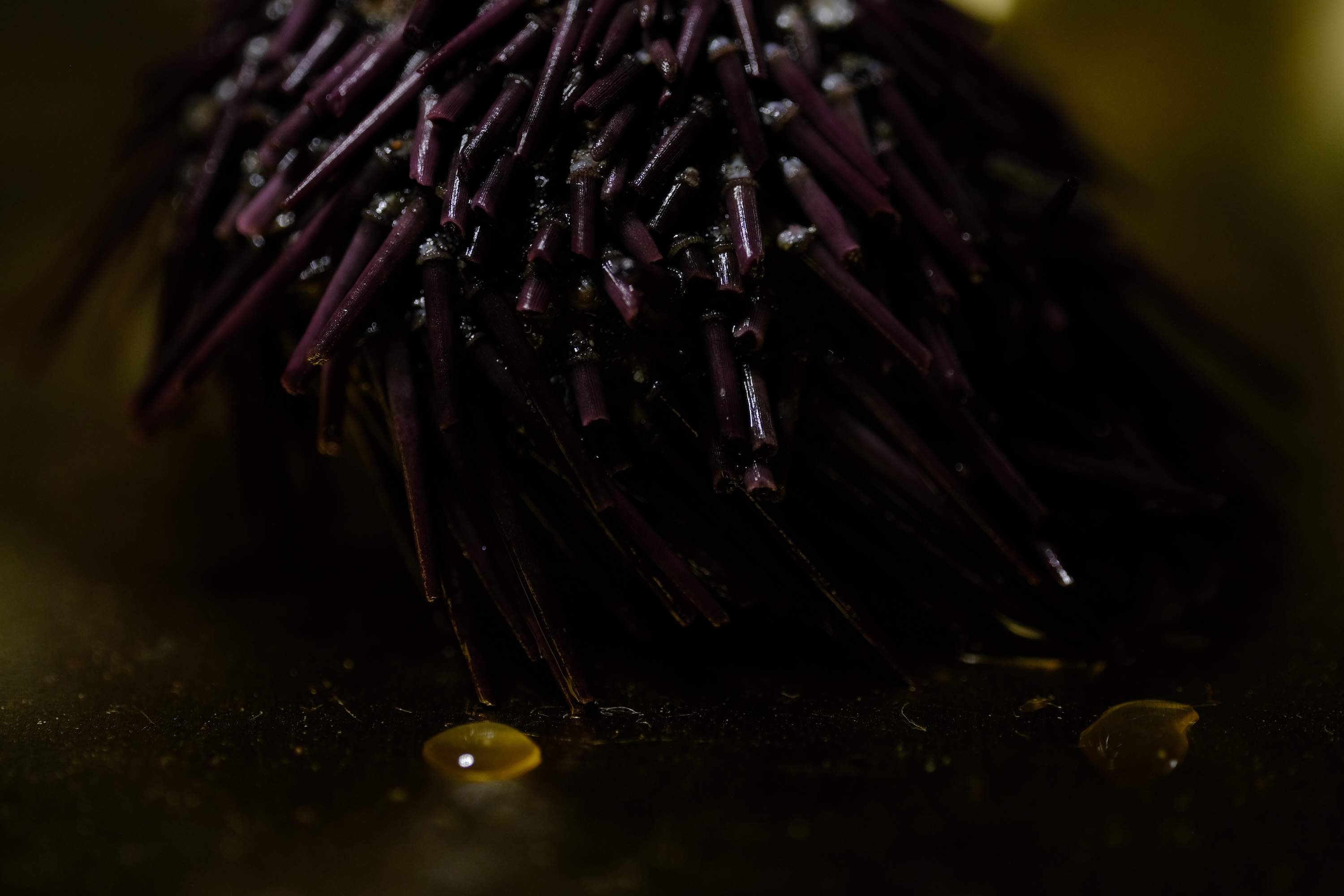

In the week after Cherry returned, the Commissioner barely saw him. She had become involute, like a snail, curled back into her spirals of repetitive form, into her phantasmic equations, into her theological pursuits. Cherry became No. 20. The Commissioner became Judith, once more. She was spiny, inscrutable, like the dead sea urchin she had found on the shore of Plumb Beach, and later buoyant, even more evidently dead. The specimen, now preserved in alcohol in a glass jar, sat at the base of a full-length mirror she had placed conspicuously in the center of a wall of her small room. She spent a lot of time looking in that mirror.

Searching on the Internet for stories of Jewish women, of Jewish women who felt fetishized, she discovered a website in which a white supremacist had compiled various pornographic images of Jewish women. The author was clearly extremely attracted to the hundred-something women he had collected and described using rather uniform, categorical, racial terms. Judith felt her cunt swelling and loosening as she read through the descriptions. The anti-semite’s passion for seeing the same trait in each of these women, in identifying these women as part of the same group, resonated with her desire to identify “rhymes” between men.

Had she become unrecognizable? The ceaseless urge for similarity, for repetition in her own object-choice, explained to Judith something of her failure to be a lover to No. 20, or to No. 17, or to No. 15, or even to No. 2. Once, as a man, she had privileged novelty above all else, and hoped to become a true poet, a demiurge. But now she was Judith. She chose expenditure as the ultimate aim. Even the Commissioner had been an accomplice to her way of life, for the object of the Commissioner’s job was to see if new structures could be built such that Judith might come back and raze them to the ground, or defile and desecrate their insides.

In the midst of this all, was the Theologian, hard at work, writing a record of their lives.

And that’s me, the Theologian, and I’d like to rest for eight hours tonight. I’ll be back!